Some background on me: I’m a software engineer working in what I call “usable security”. I’m passionate about this field because advancements can tangibly improve people’s lives, making their computing experiences easier and accounts more secure at the same time.

This post contains some of my personal thoughts. It does not represent anyone else or any organization other than me, including and especially my current employer. The purpose of this post is to educate people about the intersection of account security and usable software and to provide my perspective. I beg you not to link to or quote this post while saying that it represents any organization or company.

What’s happening?

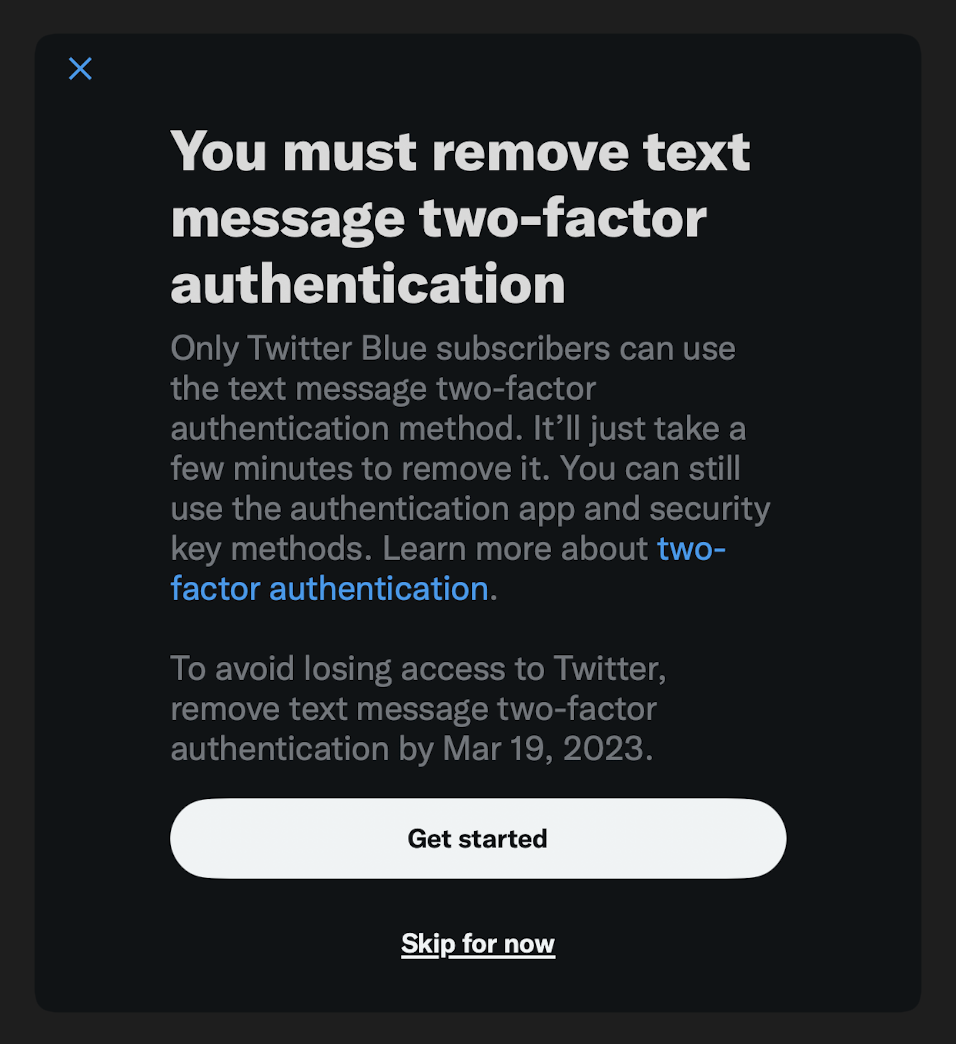

Yesterday, Twitter announced that it is discontinuing text-message two-factor authentication for accounts that don’t subscribe to Twitter Blue. And indeed, Twitter is already communicating this change to its users:

This is a huge deal for a few reasons.

First, despite the efforts of its new owner, Twitter is still a hugely important and influential service, with many notable and powerful users. We are all-too-familiar with the fact that a tweet can become a highly-impactful news story. A particular Twitter account becoming compromised can trigger real-world confusion and conflict.

And consider the years of Twitter DMs you may have and that other people have. By March 19, a month from now, up to approximately 75% of accounts using 2FA on Twitter will no longer be protected by 2FA1. That’s big.

But perhaps even more interestingly, this decision from Twitter is a big deal because it has many people who don’t ordinarily consider their security posture thinking about two-factor authentication and account security. Many people are asking questions about what this announcement means for their Twitter account and for two-factor authentication in general. Some folks are feeling blackmailed into purchasing Twitter Blue or otherwise personally under attack.

These feelings are reasonable: People’s accounts matter a lot to them, the global economic conditions mean that not everyone has the money for another subscription, and recent developments at Twitter are extremely polarizing.

In this post, I’ll explain what two-factor authentication (“2FA” from hereon in) is, what it does and doesn’t do, the benefits of text-message two-factor authentication (“SMS 2FA” from hereon in), why Twitter made this decision, how Twitter can restore some of the benefit from SMS 2FA to its non-paying users, and why passkeys will ultimately be the solution for account security for services like Twitter.

Two-factor authentication

The Account Security report on transparency.twitter.com says:

Two-factor authentication (2FA) is one of our strongest protections against account compromise. Enabling 2FA ensures that even if your account password is compromised (perhaps due to the reuse of your Twitter password on other, less secure, websites), attackers will still be blocked from logging into your account without access to the additional authentication required.

This is a good explanation of 2FA because it focuses on the impact of using it, rather than some indirect appeal to the virtues of “factors” involved in authentication. The explanation is specific, directly addressing the main threat that Twitter’s 2FA is mitigating against: password reuse.

The page continues:

In general, SMS-based 2FA is the least secure due to its susceptibility to both SIM-hijacking and phishing attacks. Authentication apps avoid the SIM-hijacking risk, but are still susceptible to phishing attacks.

This is also true, and communicated clearly. There are limitations to both SMS 2FA and “Authenticator apps” 2FA.

That said, we should not and cannot consider the effectiveness of a security mitigation without also considering its usability and its effectiveness. The “most secure” authentication scheme in the world will be limited in its impact by how accessible and user-friendly it is. The time and effort it takes for a person to set up what Twitter calls “Authentication apps” stymies their adoption. The fact that hardware security keys cost money naturally limits peoples’ interest in them.

SMS 2FA has documented and frequently-discussed limitations in terms of the security benefits it provides. It can also trip people up in terms of usability, like when people switch phones, or when they can’t receive texts at their phone number, like when they’re on an airplane, or sometimes when they’re traveling internationally.

Despite its limitations, I’ll argue that SMS 2FA is a huge success story in actually reducing the harm caused by weak and reused passwords.

The benefits of SMS 2FA

It’s pretty common to see technology enthusiasts say something like, “SMS 2FA is insecure and no one should be using it.”

I strongly disagree with statements like these because they don’t contain enough nuance, or even an acknowledgment that different people face different kinds of threats. The thinking here isn’t accurate, and inaccuracies in how people think about account security cause harm. I can’t help but read statements like these as, “Because I understand a flaw in a technology and am capable of using an alternative, no one should make use of that technology.”

A critical tool that the security community uses to think through problems is called threat modeling. Threat modeling helps with thinking through potential threats for a particular person, or group of people and ways of mitigating those threats, even if the mitigations aren’t absolute or foolproof. Threat modeling helps security teams tangibly help people without letting perfect be the enemy of progress.

People who don’t use password manager software — and that’s a lot of people — almost always reuse the same passwords across the services they use. For many of them, SMS 2FA provides value, despite its flaws. Making a person’s weak or reused password not sufficient to gain access to their accounts is genuinely good, even if a very motivated attacker could compromise the SMS channel or phish the one-time code.

Also, consider this: Your bank wouldn’t encourage or require SMS 2FA unless it mitigated real financial harm to them at scale. And scale is key. Twitter’s transparency website reports:

Over the most recent reporting period (July 2021 through December 2021):

2FA Usage

2.6% — Percentage of active Twitter accounts with at least one 2FA method enabled on average over the reporting period.

Types of 2FA

SMS: 74.4%

Auth App: 28.9%

Security Key: 0.5%

As you can see, SMS 2FA is the most prevalent form of 2FA used on Twitter. My theory for why this is is because SMS 2FA is relatively usable and accessible: lots of people understand what it means to give a service like Twitter their phone number and can figure out how to enter a code that’s texted to them.

The rub: It costs money to send text messages

Twitter’s new owner, Elon Musk, is trying to extract as much value from the service as he can as quickly as he can. This has meant finding ways to increase revenues, like pushing Twitter’s paid tier, and cutting costs, like firing large swaths of Twitter’s staff. Eliminating SMS 2FA for non-paid users is the company’s most recent cost-cutting measure. In a reply to @MKBHD, Musk writes: “Twitter is getting scammed by phone companies for $60M/year of fake 2FA SMS messages”

I will be the last person to defend how Twitter has gone about any of its recent decisions, but it’s true that the cost and fraud around SMS are real problems. During my time in the industry, I’ve worked with several organizations looking to reduce costs around sending text messages, and the costs they’ve cited have been significant. That said, none of them decided to charge for the privilege, especially after it had been a baseline feature of the service.

How could or should Twitter restore some of the benefits of SMS 2FA after having removed it?

Let’s pretend that we are account security engineers at Twitter who want to improve user security, but cannot bring back SMS 2FA to non-paying customers.

Send one-time codes via email

Emails are far cheaper to send than texts, and preserve most of the usability of SMS 2FA. A service can reasonably ask a user for their email address to use for authentication purposes and nothing else, if they don’t already have it. And then, the service can instruct a user to check their email for a code, similar to checking their texts.

In this way, one-time codes sent via email have similar usability characteristics as one-time codes sent via text.

Realize that “authenticator apps” isn’t the right framing for time-based code generators

Traditionally, to set up a time-based rotating code for 2FA, one would need to install special software like an “authenticator app”, and then follow instructions for adding a code generator.

This is no longer true, at least on one of the two dominant mobile computing platforms.

On iOS, time-based one-time code generation is built into the operating system. No “authenticator app” is required to install. Apps and websites can easily create buttons or hyperlinks to set up a new generator. (If you have a Twitter password saved to Apple’s built-in password manager, go ahead and try this link to see how easy setting up a verification code can be: Set Up on iPhone. Remember that this is a fake code.) After setup, AutoFill will take care of filling codes.

Although one of both of these approaches may be valuable in the short term, ultimately, they’re both stop-gaps.

Passkeys are the way forward

Throughout this post, I’ve been discussing ways of layering, or bolting on, additional security on top of password-based authentication. However, passwords themselves are the real problem. People need to take extraordinary care to use them in a secure way, ensuring that they’re using strong, unique passwords for every account, and that they never accidentally hand their password to the wrong entity. Not only is this bar impossibly high for casual users of technology, but even a technology enthusiast or “security expert” is vulnerable to phishing.

Passkeys are a password replacement. You can tell that from their name and the ‘pass-’ prefix. Passkeys are an industry collaboration, with advocates like Apple, Google, and Microsoft, and adopters like PayPal and Stripe. They solve the problem that Twitter is mitigating with 2FA: password reuse. In addition, critically, passkeys prevent phishing as it exists today. Rather than ask a human to decide where their account credential can be used, as is the case with passwords, passkeys are securely bound to the service they were created for.

If you’d like to see passkeys in action, please watch this four minute segment from Apple’s WWDC 2022 where I explain what passkeys are, how they work, and why they’re such a big deal.

If you’re reading this, you’re capable of and willing to set up an “authenticator app”; most people aren’t. You might be able to afford and may be willing to purchase a hardware security key; most people aren’t. Giving a service one’s phone number and occasionally entering a six-digit code is something lots of people can do and are willing to do. But ultimately, far more people can consent to save a passkey to their phone and consent to use it to sign in, and by doing so, they’ll be protected from password reuse and phishing.

Of course, no authentication technology is one-size-fits-all. For example, passkeys rely on having access to a personally-owned device and not all people who use online services with accounts own such a device, like a smartphone. But for the vast majority of Twitter’s users, passkeys are the answer.

If the topics of account security and usable software are interesting to you, it’s a lot of what I talk about over on my Mastodon account. Thanks for reading!

- My math: the 74.4% number that Twitter has published. That’s a maximum, because a non-zero number of those accounts are subscribed to Twitter Blue. Kudos to Twitter for publishing this data. The transparency benefits the whole industry. ↩