Important Note: On this blog I speak only for myself as someone experienced in usable security and website authentication. I am not speaking for the company I work for. I encourage linking to and talking about this post, but if you can, please identify me without affiliation.[1]

Independent media venture 404 Media recently published a post titled, “We Don’t Want Your Password”. The piece is a cogent explanation of the problems with password-based accounts online followed by a defense of the website’s login strategy, magic links, in the face of feedback about them being inconvenient and difficult to use.

I applaud 404 Media for having the courage to do what they feel is best for them and their customers, even if their customers may not expect it, and I give them a standing ovation for remaining resolute, but thoughtful, in the face of complaints. Passwords are deeply entrenched, and straying from the expected or default path for any kind of service, much less a media venture, is taking a risk. I’ve been meaning to write about my frustrations with and appreciation for magic links for some time now, and the steadfastness and clarity of this post pushed me over the edge to do it.

Obviously, authenticating to websites isn’t an either-or binary between passwords and magic links. Passkeys — the next-generation authentication standard defined by the FIDO Alliance and W3C, with backing from all of the major platforms, browsers, and credential managers — can be layered nicely into a magic link-based system to give users a secure and fast sign-in experience without the frustrations that come with switching apps to refresh one’s email. They’re complementary technologies, because passkeys can do this in a way that seamlessly coexists with, and is in fact supported by, email magic links for people who don’t yet have a passkey, don’t want a passkey, don’t have the device stability to use passkeys, or would prefer to sign in with a magic link this one time.

Magic Links

You’ve almost certainly encountered magic links in your time online. A “magic link” is just the special, one-time link you get emailed to you that will sign you into a website after giving it your email address. And if you’re reading this post, there’s a good chance that you use a password manager and that you find magic links to be far slower than using your password manager to sign into a website.

They frustrate me, too. My local grocery store, one of the many Albertsons companies, has taken to preferring an email magic link over my easily-AutoFilled password, and it frustrates me every single time I try to sign in. Once you’ve experienced a world where signing in to websites and apps is so seamless it requires next to no thought, while still being secure, you never want to go back.

But I also kind of love magic links, because they acknowledge — no, radically accept — some fundamental truths. Namely, that…

- almost all online accounts can eventually be signed into by proving possession of an email address; this is usually phrased as “forgot password?”

- many of the people who don’t use password managers use that “forgot password?” flow every time they sign in because people cannot use passwords effectively; why shouldn’t they just make that the user experience for everyone, or at least, the default flow?

- merely having a password for a service opens a user to attacks like credential stuffing, which is when stolen account credentials are used to gain access to accounts on other systems; credential stuffing is particularly effective because people reuse passwords

The title of 404 Media’s piece very powerfully acknowledges point 3 by saying, “We Don’t Want Your Password”, singular, acknowledging that most people have on average approximately 0.8 correct passwords in their memory at a time. And they’re willing to cop to the negative feedback they’ve gotten, writing:

Probably the most common problem people run into with magic links is they think they have logged into the site on their normal browser, but they’re actually logged in through an in-app browser. For example, someone might receive the login link to their email. They open up the Gmail app, click the “Sign in to 404 Media” button, and their phone loads the webpage. But this is loading the website in Gmail’s web browser, not your native Safari one.

In-app web browsers are unlikely to go anywhere any time soon[2], so the post describes how to work around the problem:

A solution on iPhone is when receiving the login link, click and hold the “Sign in to 404 Media” button to bring up the contextual venue, and hit “Open Link.” This will open the link, and sign you in, on your native browser. Or, copy and paste the sign in link which is also in the email.

Them calling this out is a tell; we can infer that these complaints are a real problem for 404 Media because they saw value in addressing a very specific user experience complaint. The way that their business works is that people directly pay to read their journalism; anything that stands in the way of people getting their money’s worth can impact their bottom line. I can’t say that my local grocery store’s strong preference for magic links has stopped me from being a customer, but that’s likely because I live in an area where they have an effective monopoly.

Something that I’ve learned by working on the user experience around website and app authentication is that, if you need to educate a person to go against what the inline flow naturally leads them to do, that cognitive friction will frustrate or stymie a significant number of people.[3]

Despite these drawbacks, I think that proving possession of an email address as a mechanism for signing into an online account is valuable and has its place for many, but not all, websites and apps, because email is decentralized and universal, email account providers are very highly incentivized entities to protect user accounts (e.g. Apple, Google, or Microsoft aggressively drive email account security forward), and ultimately, most people can follow instructions to check their email. This is of a kind with my belief that although it is far from ideal, SMS 2FA has its place, because authentication technology is all about threat modeling and what actually works in practice.

Passkeys

I’m going to assume that you know what passkeys are and that you’ve used them with your Google, PayPal, or TikTok account, or some other online account. If you need a refresher, I’ll plug my four minute video explanation of passkeys from a few years back that holds up pretty well today.

For the purpose of improving a passwordless authentication strategy using magic links, what’s important to remember is that passkeys suffer from none of the security problems that passwords have, and that signing in with passkeys is super fast, keeps users in their context, and never requires switching over to another app.

When it comes to speed and ease of use, in an April 2024 update on their passkey rollout, Google claimed that passkeys are 50% faster than passwords. And in my personal experience, signing in with passkey can sometimes be an order of magnitude faster than signing in with a magic link.

On iOS and Android, in notable contrast to magic links, passkeys are directly usable across web browser apps and system web view experiences. (Really. Any passkey saved and usable in Safari, whether in Apple Passwords or an app like 1Password, is usable in Chrome for iOS, Firefox for iOS, Gmail for iOS, and more.) So if a user follows a link to 404 Media in any web browser or in any email or social media app that makes use of the system web view, they can use their passkey to sign in within seconds. This is even true in web browsers like Chrome and Firefox on macOS!

The Best of Both Worlds: How to Layer Passkeys on Top of Magic Links

For a user to sign in with a magic link, they first need to type or AutoFill their email address into a text field on a website.

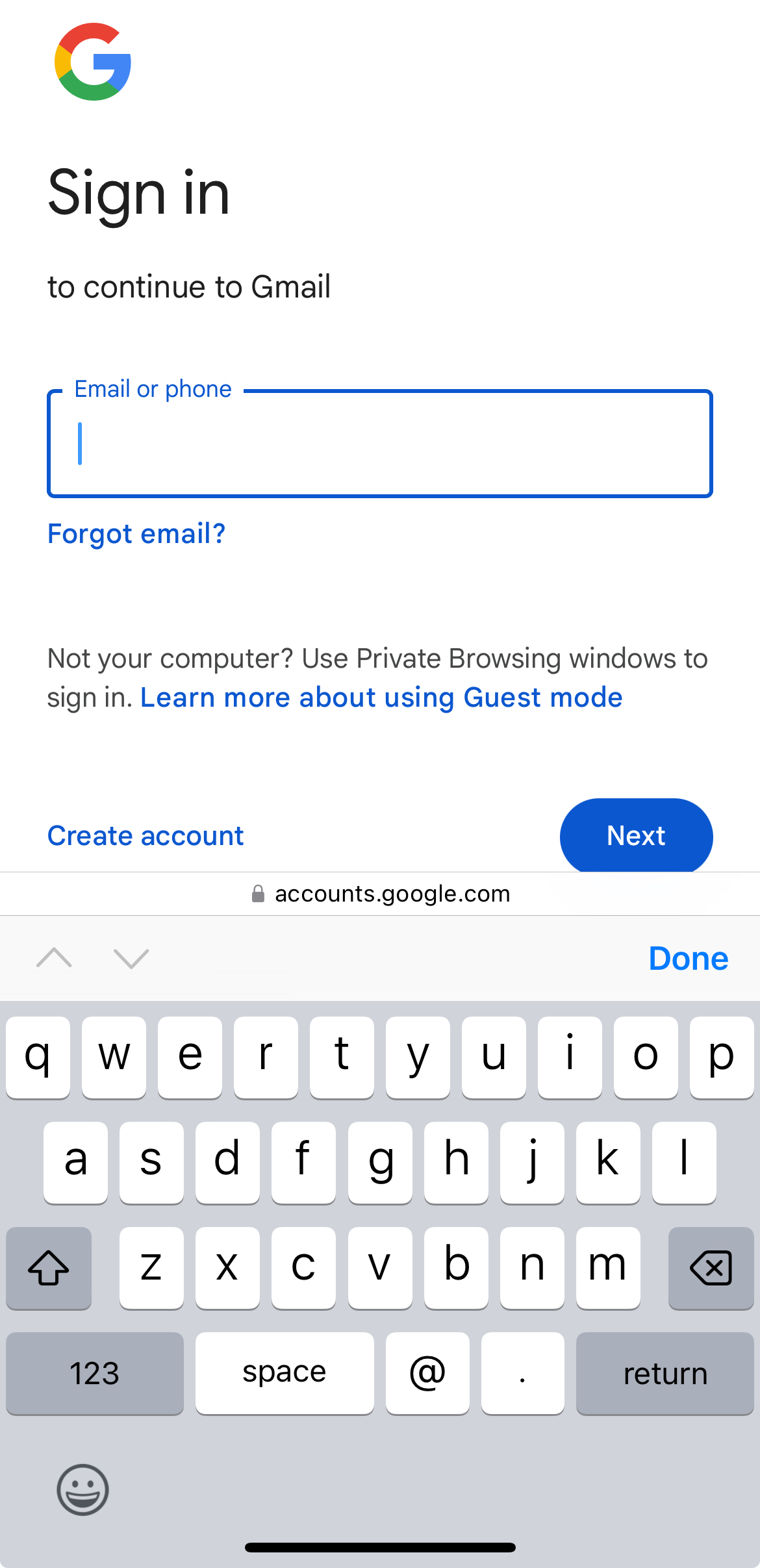

Here’s the magic: Passkeys can seamlessly integrate into AutoFill.[4] Instead of filling the literal email address, AutoFill can sign the user in with one tap and a Face ID, while behind the scenes performing the strong authentication that powers passkeys. Here’s a six-second video showing me using AutoFill and a passkey to sign into my Google account in Safari on my iPhone:

Video showing opening the Google sign-in page loading in Safari. The page has a single “Email or phone” field. Near-instantly after the page loads, an AutoFill affordance appears, saying, “Sign in to google.com with your passkey for “email@example.com”?”. It features a big blue button that reads, “Use Passkey”, and tapping it performs a Face ID that signs me in.

The most important part of this experience is that it causes zero disruptions for people who don’t already have a passkey. Here’s what’s visible in Safari on my iPhone when I don’t have a saved passkey:

You’ll notice that this looks like a totally pedestrian web form asking the user to enter their email address. The Google website has still asked the browser to help it sign in using a passkey, but since I don’t have one, I’m left to type my email address.

The website of my grocery store, as well as 404 Media’s website, could work exactly the same way, with a field for the user’s email address that is progressively enhanced to have passkey sign-in when it’s available. And all of this works without a password. (For a resource on how to implement something like this, see the footnote attached to this sentence.[5])

How to Bootstrap Passkeys on Top of Magic Links

To start, websites using magic links can make passkeys an optional, opt-in feature for the customers who have complained about how their magic links work today. To ensure it doesn’t cause any problems, as a sort of soft launch, they could make the feature 100% opt-in.

Slightly later on, once the people running the website are convinced that passkeys really help with the user experience issues around magic links, they can prompt users to add passkeys after signing in, once every 90 days or so, or whenever they sign-in using the cross-device sign-in feature of passkeys[6]. The framing of such a prompt can be something like this for users on Apple devices: Want to avoid having to check your email next time? Set up a passkey to use Face ID or Touch ID to sign in quickly and securely.

The Role of Software Platforms

The user experience and security of what I’ve demonstrated are a clear improvement over either password-based sign-in or a magic links-only experience, but in the world of running a business, nothing is free. In fact, doing literally anything at any kind of scale takes a lot more work than any of us like to think, especially for folks who have gone independent. A corporation like Albertsons may be able to afford to build and deploy passkey support, but developing and deploying a one-off feature like passkey support in 404 Media’s content management system almost certainly will not be worth the cost to them as a small business in the struggling field of online journalism.

And yet, I still wrote this post! Why is that? :)

Like a large portion of the web, 404 Media is using an open software platform (in this case, Ghost) to power their venture. If the world can convince Ghost and other platforms like WordPress and Mastodon to support passkeys, and maybe even contribute time, money, or expertise to make it happen, a huge number of people stand to benefit.

Resources

If you’re in a position to implement passkeys or influence an organization to implement them, I think it’s time to evaluate, engage with, and implement passkeys. Here are some resources I recommend you check out:

- Passkey Central: A resource for thinking through researching and planning support for passkeys in an your organization.

- Passkeys.dev: A community resource built by members of the W3C WebAuthn Community Adoption Group and the FIDO Alliance.

- Google’s Server-side Documentation for Passkeys: Comprehensive.

- Apple’s Documentation for Passkeys: Apple-platform focused.

- Google’s Android Documentation for passkeys: Android-focused.

- Google’s Chrome Documentation for Passkeys: Web-focused.

I’m also personally happy to answer questions and talk with folks considering adopting passkeys. I’m serious — hit me up.

Takeaways

I want to see my friends, family, and people who I will never meet no longer harmed by passwords, and I have dedicated the last five years of my career to dethroning them as the default credential for websites and apps. Passkeys aren’t perfect, because nothing is, but myself and other members of the FIDO Alliance are always listening to feedback and working to improve them. And as they exist today, they can clearly make the experience of signing into websites faster and easier than before.

Again, if you have questions about passkeys or authentication technologies in general, feel free to hit me up on Mastodon or Bluesky. I hope you learned something, and thanks for reading!

-

As you can tell, I am taking great pains to not have my blog meaningfully affiliated with my employer. I am doing this to respect my employer’s desire to not have employees interpreted as speaking for the company when they are speaking only for themselves. As a proud member of technology standards organizations with noble goals, and as an independent person, I hope I can help the industry by contributing my perspective from time to time. If being pressured to not emphasize my employer in a link post dissuades you from linking to it, then I didn’t deserve your link in the first place. :) ↩

-

The incentives, economics, and privacy considerations around in-app web browsers is a fascinating and important story, but one I am not able to tell. ↩

-

If you’ll give me some leeway, I think it’s analogous to password management software in that password management software has a ceiling to the number of people it can help, because fundamentally, it is laying instructions and a process on top of websites and apps that expect people to create and type passwords by hand. The dissonance that I’m describing here is similar to the difficult to remember to do advice to copy and paste a sign-in link that is screaming to be tapped. This advice is almost begging you to inhabit the mental model of how browser cookies work, which is something that normal people shouldn’t have to do.

This ceiling for the number of people password management software can help is part of why I believe so strongly in passkeys. A single, attractive affordance for signing in can confuse fewer people than whatever a password manager lays on top of a web page. ↩

-

In WebAuthn parlance, the use of passkeys with the AutoFill user experience is called “conditional mediation”. It’s not just a powerful tool for integrating with magic links, but also with existing password-based sign-in experiences. ↩

-

WebAuthn Conditional UI (Passkeys Autofill) Technical Explanation, a post from the Cordabo blog, goes into detail on how to implement conditional mediation for passkeys. ↩

-

As demonstrated in the four minute video I linked to, passkeys can be used to sign in across devices. So I can use a passkey on my iPhone to sign into a website on a Windows PC. Websites can detect when this happens, and should turn around and ask the user to register another passkey on the “new” device. ↩